Report: 1 in 4 Data Breaches Exploit Third-Party Vulnerabilities

Plus, AI-powered phishing campaigns represented over 80% of social engineering events in 2025.

Latest News

See all news-

Anthropic Alleges DeepSeek, MiniMax Trained Models With Claude

Anthropic says the campaign led to "over 16 million exchanges with Claude through approximately 24,000 fraudulent accounts."

-

90% of Businesses Say AI Had No Impact on Job Losses

Usage still remains high, though, with 78% of US businesses using the technology on a regular basis.

-

Report: 48% of Fleets Want Asset Tracking Amid Cargo Theft Surge

Nearly half of fleet professionals aim to adopt asset tracking systems, with 48% saying they are looking to get the tech.

-

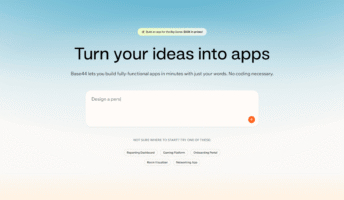

Base44 Users Can Finally Publish Creations to App Store

Base44 added a whole bunch of new features to its vibe coding platform after its Super Bowl ad.

-

Report: 61% of EV Trials Are On Hold After New Lax Fuel Rules

Our recent data suggests that logistics professionals are more influenced by government policy than sustainability goals.

-

Gartner: Tighten Up AI Governance or Face the Consequences

Gartner has published its cybersecurity predictions for 2026 — and companies need to tighten up their AI agent oversight.

About Tech.co

At Tech.co, we understand that tech decisions can make or break your company. Whether you’re looking to buy software that will level up your business, or want to understand the latest issues affecting your industry, you need experts who can give you the inside track.

That’s where we come in. Tech.co has a 20 year legacy of offering invaluable advice to businesses. We’ve helped thousands of companies to thrive within the constantly moving tech landscape through our professional analysis, insightful research and industry expertise. Every step of the way we ensure our guidance is helpful and comprehensible.

Logistics Tech

Changes in the Road Ahead: Trucking Regulations to Look Out For in 2025

In this guide, we've unpacked all of the biggest trucking industry regulations that are coming your way.

-

How Tech Is Solving the Truck Parking Crisis

There is one spot for every 11 trucks in the US, and 98% of truckers have had a hard time finding parking.

-

What Is Autonomous Truck Platooning and How Does It Work?

With automated trucks on the horizon, "platooning" is in the spotlight. But what actually is it and how does it work?

-

Top Logistics Scams to Look Out For

Logistics scams can be a huge detriment to the success of your business, which is why avoiding them needs to be a priority.

-

10 Logistics Influencers You Need to Follow in 2025

Looking to get inspired and stay ahead of the logistics curve? Here are the influencers that can help you out.

-

Why Large Scale Drone Deliveries Could Soon Be Reality

With big names behind them, is it finally time for drone deliveries to take off and become a serious last mile option?

-

5 Startups Bringing Sustainability to Logistics

Wood processing waste, RFID tags made out of paper, and smart waste sensors are just a few unexpected innovations.

Moving Goods With Fewer Hands: Tech.co Logistics Report 2025

Download the Tech.co Logistics Report to learn more about the pressures facing the US logistics industry in 2025.

Hospitality Tech

6 Best Restaurant POS Systems 2026: Which POS Is Best?

Whether you're a full-service restaurant or fast food chain, our research and tests will determine the best POS for you.

-

Yelp Reaches for AI to Deliver Better Restaurant Reviews

New AI-powered review insights can deliver key information on topics like service, ambiance, and food quality.

-

QuickBooks Online Pricing: How Much Does QuickBooks Cost?

QuickBooks Online pricing is always changing, so make sure to stay up-to-date on how much this accounting software costs.

-

Best Cash Registers for Small Business: Which POS System Is Best?

Cash registers are essential for small businesses. We break down the best POS and traditional options on the market.

Professional Services Tech

Salesforce Pricing 2026: License Costs and AI Fees

The popular CRM has increased its prices. Here's what Salesforce costs in 2026 and what you get for your money.

-

Best Multi-Line Phone Systems for Your Business – Comparison Guide

Today's multi-line phone systems offer great flexibility and call quality, with no need for endless equipment.

-

11 Best Paid and Free Alternatives to Google Voice

If you think Google Voice is good but not great, here are the best alternatives to consider switching to.

-

Best Project Management Software – Comparison Guide 2026

We review some of the top project management software platforms, so you can make the right call for your business.

-

Best International Phone Call Apps – Rates & Features Compared

These apps offer business and personal use options to help you stay connected with people all around the world.

-

5 Cheapest VoIP Phone Services for Small Businesses in 2026

Our independent research found that Zoom is the best cheap VoIP phone service in 2026, followed by Google Voice and Dialpad.

-

Smartsheet Pricing – How Much Does Smartsheet Cost?

We take a look at Smartsheet's main pricing plans and add-on costs to help you choose wisely.